The Hunt for the Thylacine: A Tragic Tale of Extinction

The Tasmanian tiger, once a shadow, now only a whisper, roamed the island of Tasmania with the silent grace of a predator. Thylacinus cynocephalus, its scientific name, evokes both awe and sorrow—a reminder of a species that disappeared too soon. The last known thylacine died in captivity at the Hobart Zoo in 1936, the victim of human expansion. Today, Tasmania stands quiet, haunted by the ghost of a creature that could have been.

|

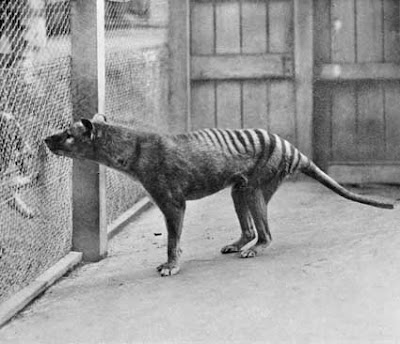

| The Last of Its Kind: A Thylacine at Hobart Zoo, 1933. |

The Silent Vanishing: A Hunter's End

The first recorded sighting of a thylacine by Europeans was in 1642, when Dutch explorer Abel Tasman arrived on the island. However, it wasn’t until the 19th century, with the arrival of British settlers, that the thylacine’s fate was sealed. Farmers brought livestock with them, and the thylacine was soon seen as a threat to their flocks. In 1830, a bounty was placed on the thylacine’s head, offering a reward for every one killed. The government-backed hunt, fueled by fear and misunderstanding, drove the species toward extinction.

The settlers saw the thylacine as a menace, a creature that could ruin their livelihoods. They used rifles, traps, poison, and dogs to hunt the thylacine. The species had few defenses against this onslaught. By the early 1900s, the thylacine population had already begun to shrink. In 1901, the thylacine was declared a protected species, but it was too late. The damage had been done. Poaching continued, and the last known wild thylacine was captured in 1930.

The final blow came in 1936.The last known thylacine, a female, died from neglect in captivity at the Hobart Zoo.. With her death, the species was lost. Gone was a predator that had evolved over millions of years to fit perfectly into Tasmania’s ecosystems. It had played its part in controlling the populations of smaller animals, maintaining balance in a world now altered by humans.

The thylacine’s extinction was not just the loss of an animal; it was the loss of an ecological role. Extinction is not only the end of a species, but the erasure of its place in the world. The thylacine was not an invader; it was a product of the land, shaped by its environment. But it was wiped out by the advance of settlers, whose actions were motivated by fear and a desire to control nature. In hunting the thylacine, they erased an important piece of Tasmania’s natural history.

The thylacine was more than just a predator—it was a story written in the bones of the earth. It was a creature that lived in balance with the land, until humans misunderstood it. To honor the thylacine is not to resurrect it, but to remember what we lost. We must learn from its extinction. We must understand that in our attempts to control the wild, we must never forget that we are part of it too. Only by respecting that truth can we protect the fragile threads that remain.

The video above is rare footage of thylacines filmed between 1911 and 1933 at Hobart Zoo, Tasmania, and London Zoo, offering a glimpse into the lives of these now-extinct marsupial predators. Below is a restored colorized image of the last known surviving thylacine. The NFSA has released this footage, bringing the memory of the Tasmanian tiger back to life in color. Wikipedia.org/wiki/Thylacine